Cowboys Real and Imagined

New Mexico History Museum

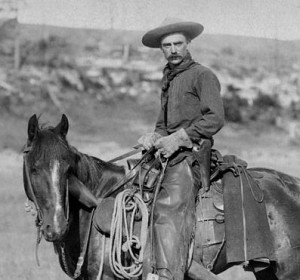

When America needed hard workers, the cowboy was there. The job was dirty and difficult, low-paid and lowly regarded. But when an America torn by the Civil War needed a hero to unite its soul, the unassuming cowboy was an unlikely—and ultimately lasting—pick.

Since riding out of Spanish horse culture, he’s been an itinerant hired hand, an outlaw, a movie star, a rodeo athlete, a radio yodeler, and a rhinestoned disco diva. He’s been Spanish, Mexican, African American, Anglo, male, female, straight, and gay. His image has been co-opted to sell trucks, beer, boots, beans, jeans, tires, cigarettes, leather couches, presidential candidates, and a lifestyle far beyond the means of real-life buckaroos.

Despite the sometimes tortured lengths our imaginations have taken cowboys and cowgirls, the basic fact of their life is this: a rough-hewn job stacked against steep odds. The daily dangers of working with cattle and horses are matched by volatile global markets, a public with fickle tastes in heroes, and a big sky that can deliver sunshine and tornadoes, droughts and snowstorms.

Today, real cowboys sit uneasily in the saddle (or on the seat of an ATV, occasionally dubbed “a Japanese cutting horse”). Climate change has altered the range and dealt cattle-ranching a potential kill card. Even as popular culture delivers new-and-improved versions of a fanciful life on the range, Cowboys Real and Imagined asks a bare-boned question: Will the people who tamed that range survive?

Download high-resolution images from the exhibition by clicking on “Go to related media” at the bottom of this page.

Using artifacts and photographs from its wide-ranging collections, along with loans from more than 100 people and museums, Cowboys Real and Imagined (April 14, 2013, through March 16, 2014) blends a chronological history of Southwestern cowboys with the rise of a manufactured mystique as at home on city streets as it is in a stockyard.

Augmented by archival footage, oral histories, musical performances, and a programming series that includes showings of classic Western movies filmed in New Mexico, the exhibition anchors the cowboy story in New Mexico, a place that not only helped give birth to the real thing but, due to geographical and economical factors, has managed to hold onto it longer than most other states.

“One of the reasons the cowboy myth has been so pervasive and long-lasting is because anybody could become a cowboy of sorts,” said guest curator by B. Byron Price director of the Charles M. Russell Center for the Study of Art of the American West at the University of Oklahoma and director of the University of Oklahoma Press. “It isn’t always what you wear, who you are, or what your attitude is. The exhibit asks: Who is a real cowboy?

In its search for an answer, Price said, the exhibit discovers that cowboy “is a verb, an adjective, a noun, an adverb.”

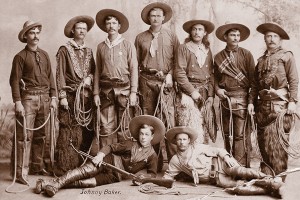

Despite a career devoted to exploring the story of the cowboy, Price said he was amazed at what he found in the museum’s Palace of the Governors Photo Archives, including a small cache of glass-plate negatives. Made by Ella Wormser, the wife of a Jewish merchant, they may be the only visual evidence of trail drives making the transition toward rail transport.

“I’ve spent years studying this and I haven’t found any better material than here at the New Mexico History Museum. In New Mexico, because the old style of cowboying still prevails, that attracts photographers—contemporary photographers.”

Modern-day shooters represented in the exhibit include Barbara Van Cleave, Lee Marmon, Donald Woodman, and Herbert Lotz. Other artifacts include cowboy clothing from the 1700s through contemporary times; the chuck wagon that once fed cattle-driving cowboys of the northeastern New Mexico’s famed Bell Ranch; ephemera from the dude ranches that once speckled the state; and the ads that banked on cowboys to sell products. People who pop up through the exhibit include legendary Lea County cowgirl and rancher Fern Sawyer; singer Louise Massey; actor and film producer Tom Mix; Buck Taylor, “The King of the Cowboys”; Billy the Kid; Frederic Remington; and the anonymous Rough Riders, cowboys, and vaqueros whose real-life acts still feed a wide-open space of the American dream.

As part of the exhibit, the Palace Press is preparing a fine-press version of Jack Thorp’s classic Songs of the Cowboys, first published in Estancia, NM, in 1908, on a press now used at the History Museum. Thorp’s was a pioneering compilation of songs he heard hummed and strummed around campfires in New Mexico and included tunes from African American cowboys. Most of what he recorded likely would have faded into the starry skies without that effort.

Cowboys Real and Imagined is generously supported by the Brindle Foundation; Burnett Foundation; Rooster and Jean Cowden Family, Cowden Ranch; Jane and Charlie Gaillard; Albert and Ethel Herzstein Charitable Foundation, Houston; Candace Good Jacobson in memory of Thomas Jefferson Good III; Moise Livestock Company; Newman’s Own Foundation; New Mexico Cattle Growers’ Association; New Mexico Humanities Council; Palace Guard; Eugenia Cowden Pettit and Michael Pettit; 98.1 FM Radio Free Santa Fe; and the many contributors to the Director’s Leadership, Annual Education, and Exhibitions Development Funds.